125 years after the landmark ruling, Plessy and Ferguson descendants and the New Orleans district attorney are seeking a posthumous pardon.

On 7 June 1892, an act of bravery undertaken by a free man of color in segregated Louisiana had historic consequences.

Homer Plessy, a New Orleans shoemaker of mixed heritage, purchased a first class rail ticket and boarded a train bound for Covington. He took a seat in a whites-only car and declared to the conductor that he would not move. The planned act of civil disobedience was orchestrated by a local civil rights organization to challenge the Louisiana Separate Car Act, one of a number of segregationist laws passed in the post-Reconstruction south.

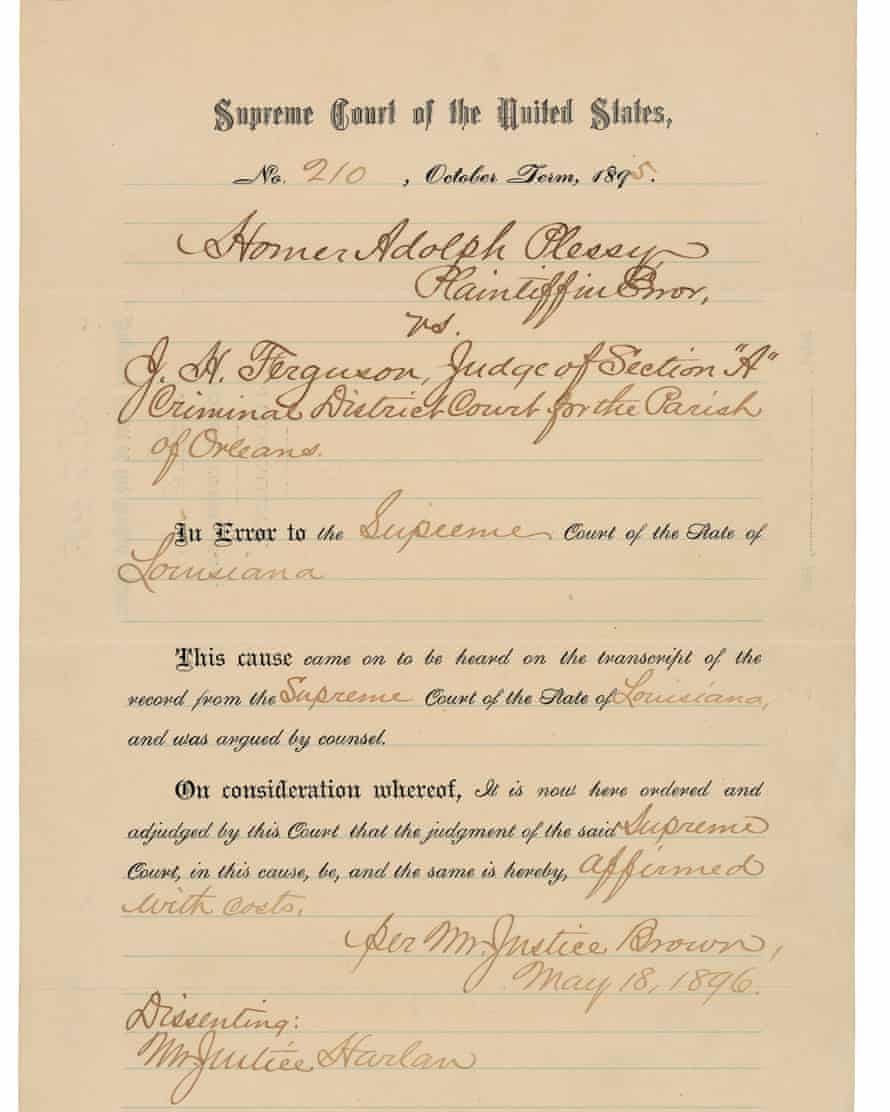

His case eventually ended up before the nation’s highest court and resulted in a landmark 1896 ruling that defined the Jim Crow era and legalized racial segregation in America.

But now, 125 years since the Plessy v Ferguson decision, a coalition including Plessy’s descendants, ancestors of John Ferguson, the Louisiana judge who originally tried the case, and the New Orleans district attorney’s office who prosecuted him over a century ago, have commenced efforts to posthumously pardon Homer Plessy.

The request for a pardon was officially made on Friday morning, at a Louisiana parole board hearing. The board voted unanimously to recommend the pardon, leaving the final decision with the state’s governor John Bel Edwards. The Guardian was given access to the application before submission.

“When Homer Plessy died in 1925 everyone remembered his name as somewhat the poster child of segregation,” said Keith Plessy, a distant first cousin of Homer Plessy and a signatory to the pardon request. “And this stigma can be removed from his memory by honoring him in the right way. By recognizing that the law itself was a crime.”

After the supreme court’s decision in 1896, Plessy was criminally prosecuted and changed his plea to guilty for violating the Separate Car Act. He was made to pay a $25 fine. Unlike civil rights activists who would go on to utilize the same tactic of challenging laws by direct action, he slipped away from public life.

“If the pardon is granted and the governor of Louisiana signs it, it will show a willingness of our state government to recognize the devastating effect the enactment of the separate car law had on Black citizens in Louisiana,” said Phoebe Ferguson, judge John Ferguson’s great-great-granddaughter and another signatory to the application. “It will show that even 125 years later an apology for enacting those laws can have great effect and for other laws to be overturned or examined and for others to receive a pardon.”

The application for Plessy’s pardon has been brought under a little-known 2006 Louisiana statute, the Avery C Alexander pardon law, named after the late civil rights leader and state politician. The law mandates that any person convicted under a local law to maintain or enforce racial separation or discrimination is eligible for pardon, with the parole board required to submit the application to the state governor within 14 days unless there are objections. Louisiana’s governor, Democrat John Bel Edwards, will then decide the matter unilaterally.

The New Orleans district attorney’s office believes this is the first time the law has been used since its enactment.

The pardon application is supported by the New Orleans district attorney, Jason Williams, a progressive elected last year on a campaign of sweeping criminal justice reform in a city known as one of America’s incarceration capitals. It was managed by a newly created civil rights division in his office, tasked with re-examining cases prosecuted by previous administrations.

In an interview with the Guardian, Williams described the original decision to criminally pursue Plessy after the supreme court decision as an example of a “token prosecution by my predecessors”.

“They didn’t have to demand a conviction, and they should not have demanded one,” Williams said. “District attorneys then and now have the discretion to decide who to prosecute and who not to.”

He continued: “They wanted to make him [Plessy] a symbol of the challenge against segregation and white supremacy, to show that Jim Crow was going to be the law of the land.

“There is no more glaring example that exists of that abuse of prosecutorial discretion than Homer Plessy’s prosecution.”

The move to pardon Plessy follows years of advocacy work by the Plessy and Ferguson foundation, of which Keith Plessy and Phoebe Ferguson are president and executive director respectively.

The foundation has previously petitioned the city of New Orleans to hold an annual Homer Plessy Day to mark the anniversary of his arrest and to rename the street near the railway tracks Homer Plessy Way. A brown historic plaque that tells the story of Plessy’s act of civil disobedience was erected at the spot of his arrest in 2009.

Plessy and Ferguson met for the first time in 2004 at an event launching a book on the case. Plessy recalled the meeting, in which Ferguson apologized to him for the legacy of slavery and segregation in the state. “I had to stop her and say ‘hey you know we were not born then. It’s no longer Plessy versus Ferguson, this is Plessy and Ferguson.’”

He added: “As children coming up in New Orleans we were in two different worlds, almost. But now we’re almost joined at the hip.”